In common usage a transducer is a device that converts one kind of energy to another. Wikipedia lists a fantastic variety of transducers, mapping out links between thermal, electrical, magnetic, electrochemical, kinetic, optical and acoustic energy. In this form transducers are everywhere: a light bulb transduces electrical energy into visible light (and some heat). A loudspeaker transduces fluctuations in voltage into physical vibrations that we perceive as sound.

In analog media, transduction is overt (put the needle on the record...). But digital media are riddled with it too. Inputs and output devices all contain transducers: the keyboard transduces motion into voltage; the screen transforms voltage into light; the hard drive mediates between voltage and electromagnetic fields. A printer takes in patterns of voltage and emits patterns of ink on a page. Strictly transduction only refers to transformations between different energy types; here I want to extend it to talk about all the propagating matter and energy within something like a computer, as well as those between that system and the rest of the world. From this transmaterial perspective a computer is a cluster of linked mechanisms and substrates; a machine for shifting patterns through time and space.

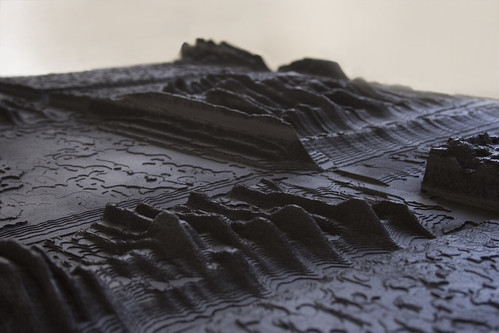

If this sounds unfamiliar, it's only by historical accident. Mechanical computers, where these patterns are physically perceptible, predate electrical (let alone digital) ones, by centuries (above: a replica of Konrad Zuse's Z1, a mechanical computer from 1936. Image by rreis). Materially, our current computers are more or less black box systems. Their transductions come as a sort of preconfigured bundle or network, a set of familiar relations constructed again by mixtures of hard- and software, protocols, standards: generalising frameworks. I press a key, a letter appears; this is all I need to know. Click "OK". No user-serviceable parts inside.

Except that currently, across the media arts and a whole slew of other fields, the computer is undergoing a rich and productive decomposition. It's composting, to borrow a Sterlingism. This goes under all kind of different names: hardware hacking, device art, homebrew electronics, physical computing. Such practices mount a direct assault on the computer as a material black box, literally and figuratively cracking it open, hooking it up to new inputs and outputs, extending and expanding its connections with the environment. Microcontrollers like the Arduino present us with nothing but a row of bare I/O pins. Finally we can tackle the question of what should go in, and what should come out: of transduction. A whole generation of artists, designers, nerds and tinkerers are taking up soldering irons and doing just that. Below: the Spoke-o-dometer from Rory Hyde and Scott Mitchell's Open Source Urbanism project.

One side-effect of this decomposition of computing is that the ontological status of the digital starts to break down with it. As Kirschenbaum shows brilliantly, the digital is just the analog operating within certain tolerances or threshholds. Thomas Traxler's The Idea of a Tree (below) is a solar-powered system that fabricates objects from epoxy, dye and string, by turning a spindle. Solar energy generates electrical energy, which drives the motor, which draws the string through the dye and onto the spindle: a chain of analog transductions produce an object that manifests specific changes in its local environment. The work is a beautiful demonstration that variability doesn't have to be worked up with generative code: if the system is open to it, it's already there in the flux of the material field.

This is not to dismiss computing, only to recast it: an incredibly dynamic, pliable set of techniques for manipulating the material environment. Paradoxically the very generalities of computing - the abstractions and protocols that insulate it from local, material conditions - make it a powerful tool for transduction, that is, the propagation of specificities. Usman Haque's Pachube is a generalised infrastructure, a set of protocols and standards that rest in turn on wider standards like XML, and which assume a whole stack of functional layers: IP, HTTP, and so on. All in order to propagate material patterns and flows from here to there: this is an architecture of transduction whose utopian aim is to "patch the planet" into a translocal ecology of linked environments.

Digital fabrication is part of the same shift: an expansion and extension of the computer's range of material transductions. Digital pattern, to lasercutter instructions, to physical form. Fabbing shows how material matters. It's unsurprising that a piece of laser-cut ply is aesthetically different to a luminous pattern of pixels; more interesting is the way computation reaches out into the substrate's material properties, and the range of potential applications and domains it opens up. Fabbing has often presented itself with a narrative of materialisation, making the virtual real, translating bits into atoms - Generator.x 2.0 was subtitled "Beyond the Screen." Not so: because of course, the "virtual" never was, and the screen is material too. Fabbing does get us beyond the screen, but only because its processes and materials have different properties, different specificities, and they hook us up to new contexts, as well as new sensations. (Below: Andreas Nicolas Fischer & Benjamin Maus: Reflection - from 5 Days Off: Frozen)

Transduction suggests a way to link practices like physical computing, fabrication, networked environments, and many more. Data visualisation - in the broadest sense, from poetic to fuctionalist - is about creating customised transductions, sourcing new inputs and/or manifesting new outputs (even if they don't reach "beyond the screen"). We could add tangible interfaces, augmented reality, and locative systems. What does all this amount to? In 1970 Gene Youngblood observed a similar moment as the dominant cultural form diversified into a networked, participatory, interdisciplinary field of practices. He called it expanded cinema. So perhaps we can call this expanded computing: digital media and computation as material flows, turned outwards, transducing anything to anything else.

3 comments:

The same way DIY physical computing a la Arduino is a physical assault on "computer (hardware) as black box", I feel like databending & glitch work is an assault on "computer (software) as black box".

Yep, absolutely, except I'd argue in a kind of obstinate way against the software/hardware distinction. Glitch / databending is exactly about rerouting the default transductions of a digital (material) system. One implication of this idea (yet to be fleshed out) is what software is, in this formulation. Contra Kittler, it *is* really there, but maybe it's something like a meta-pattern - a material pattern that spawns, manipulates and integrates other patterns. So then in databending, opening a Word file in Photoshop becomes a sort of material flow rather than a software operation. It's a fairly laborious conceptual workaround, but I think it might be worth it...

I find it fascinating that this approach extends the concept of materiality in art beyond the purely phenomological qualities. As such it raises questions about the connnection between materiality and aesthetics.

Post a Comment